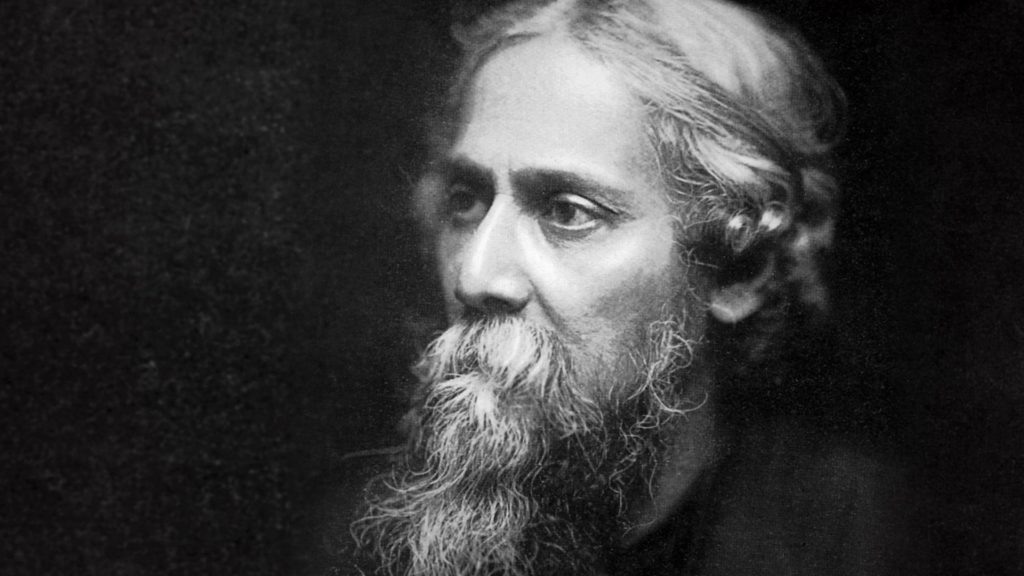

In seeking some solace and inspiration the other day, I turned for refuge to the work of Bengali laureate, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). My logic was in times of difficulty and decline some greater perspective may be derived from those who have seen a vastness of ascendency and descent, and decency and assent, in civil society.

Superiority in Silence

My first turning turned over a letter written in 1893 on the topic of whether it is better to pay homage to the present norms of superiority or to remain in silence until one’s own voice finds significance. From a place of disenchantment with existing social norms, Rabindranath observed:

“When we establish ourselves in the world, when we can contribute to the work of the world, only then shall we be able to smile and talk with them. Until then it is better to hide away and shut up and keep doing our own work.” (2011, p. 92)*

The difficulty identified is when forming and establishing a new voice, there are so few to talk with in the meantime. Tagore writes of Sholapur (in that time):

“It is very difficult here to keep one’s strength of mind. There is no one to really help you. You cannot find anybody with whom to exchange a few words and feel alive within ten or twenty miles – nobody thinks, nobody feels, nobody works; nobody has any experience of a great work or a life worth living; you will not be able to find a mature humanity anywhere.” (2011, p.92)

It was this stunning phrase ‘… a mature humanity ‘, perhaps a quirk of translation, that begs an empathy in me for Tagore’s search when saying: ‘One feels a real mental thirst to be in the company of a real humanity …‘.

This led me to ask how is it that we, as a humanity, may have matured since the 1890’s – and are we now in greater company and companionship in our humanity of civility.

Self and Sacrifice

By jumping forward to the pre-war context of 1913, we might search for our greater maturity within Tagore’s own musings. As if echoing the disenchantment of a modern ‘me-generation‘ addiction to selfie-ness, his essay ‘The Problem of the Self’ holds a key insight on the linkage between the choices in the ‘reveal’ of the self and the ‘revelation’ of self-hood:

“At first sight it seems that man counts that as freedom by which he gets unbounded opportunities for self-gratification and self-aggrandisement. But surely this is not borne out by history. Our revelatory men have always been those who have lived the life of self-sacrifice. … We can look at our self in two different aspects. … To display itself it tries to be big, to stand upon the pedestal of its accumulations, and to retain everything to itself. To reveal itself it gives up everything it has, thus becoming perfect like a flower that has blossomed out from the bud, pouring from its chalice of beauty all its sweetness.” (2011, p. 161)

This portrayed for me the clear contrast between the faux largesse of public pedestals and the small blossoms of inquiry’s own inner petals. To reveal the self, one does not need to revel in self-prominance.

Civility Re-Dawning

Moving forward once again in time to the catastrophes of 1941, Tagore is faced with a more brutal reflection on service and sacrifice on the losing of civilisation:

“As I look around I see the crumbling ruins of a proud civilisation strewn like a vast heap of futility. And yet I shall not commit the grievous sin of losing faith in Man. I would rather look forward to the opening of a new chapter in his history after the cataclysm is over and the atmosphere rendered clean with the spirit of service and sacrifice. Perhaps that dawn will come from this horizon, from the East where the sun rises. A day will come when unvanquished Man will retrace his path of conquest, despite all barriers, to win back his lost human heritage.” ~ ‘Crisis in Civilization’ (2011, p. 216)

This raised for me the idea that as man vanquishes man (and innocence is trampled in the terrorising of the innocents) there might be a horizon-in-time where the unvanquished spirit of Mankind itself arises, from our vanquishing of others of our kind.

Humility in Nobility

So from occupations to warnings, from war to occupation, and into the pre-occupations that occupy us over the winding course of the transitions in an engaged life, we find simpler guidance.

From the many roles Tagore held, as translator, poet, dramatist, writer, composer, painter, speaker and traveller, it was perhaps as a teacher of children where he received the greatest tuition.

His speech on acceptance of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, reveals perhaps where the best inspiration for being in service to humankind is found:

“And in the evening during the sunset hour I often used to sit alone watching the trees of the shadowing avenue, and in the silence of the afternoon I could hear distinctively the voices of the children coming up in the air, and it seemed to me that these shouts and songs and glad voices were like fountains of life towards the bosom of the infinite sky. And it symbolized, it brought before my mind the whole cry of human life, all expressions of joy and aspirations of me rising from the heart of Humanity up to this sky. I could see that, and I knew that we also, the grown-up children, send up our cries of aspiration to the infinite. I felt it in my heart of hearts.” (2011, p. 185)

… and so Tagore came out of his ‘silence’ and offered nourishment to the West.

Child’s Delight

From this guidance we might look further into the comedy of our times with not other than a child’s delight, avoiding the sagaciousness of a sage’s despair. For in his poetry and eloquence the humour and playfulness of the comedic verses of Tagore can hold equally profound sets of wisdoms and musings.

The re-telling by Tagore of an old fable known as the ‘Invention of Shoes‘ – speaks of a King who ‘waged war against the dust’ that might fall on his royal feet. The King’s minister acted swiftly in attending to this task and asked wise men from far and wide what to do. They suggested ‘to cover the earth with mats‘, to ‘smother the soil with carpeting‘, or to lock the King ‘in an airtight room‘ – before deciding to wrap the earth in leather.

When faced with the dilemma of how to find leather ‘hides enough to match their need’ an aged master leather-smith replies:

“O Sire, If you kindly allow, I can tell you how,

To easily gain your heart’s desire.

Just cover your feet and it will be found,

That there is no need to cover the ground.” (2011, p. 743)

And so, this is how ‘footwear had its birth’, and the King’s minister was spared, and so was the Earth.

Prospective Humanity

In looking for similar encouragement, if one is to write in the field of humanity-caring, there are not many voices and minds asking about the questions of skilled application, let alone conceiving of the prospects of the vastness of this humanity-caring.

From silent work in this field since 1999 there have been many words and discourses, discussions and curations, but the world has appeared to be pre-occupied with the ‘dust on its feet’ and the process and prospects of individual self-aggrandisements.

As we move forward into times anticipated, heralding great conflicts like those seen in 1891, 1913 and 1941, I might take from Tagore’s own humbled learnings to find in the encouragement of children’s laughter, the fact that we all in truth make our own pathways.

To do this end the lesson of instruction, as contained in Buddhist Dharma, is not to try to cover the world in leather, but rather to look first to how one needs to walk in one’s own footsteps of contribution.

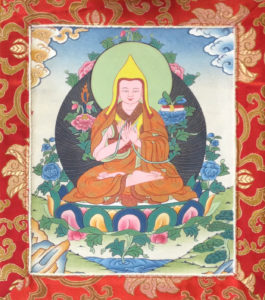

In renowned Tibetan scholar Je Tsongkapa’s (1357–1419) ‘The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment’ there is a quote from the text on Engaging in the Bodhisattva Deeds, which reads (with reference to the development of true patience):

“Undisciplined persons are as limitless as space; You could never overcome them. If you conquer the single mental states of anger. It is like vanquishing all your enemies. Where could you get enough leather, To cover the entire surface of the earth? Wearing just the leather of your sandals. Is like covering all the earth. Similarly, I cannot change external things, but when I can change my state of mind, Why do I need to change anything else?” (Vol. 2, Ch. 12, p.*)

This brought me full circle back to the source of my own refuge in strange times.

For the patience we require is not with the absence of civility and civilisation in all men, but is rather the development of equanimity and equality, in our own natures, with all of humankind.

* Source: Alam, F. & Chakravarty, R. (2011) ‘The Essential Tagore’, Harvard University Press: Mass.

© willvarey (2016)